Practical number

In number theory, a practical number or panarithmic number[1] is a positive integer n such that all smaller positive integers can be represented as sums of distinct divisors of n. For example, 12 is a practical number because all the numbers from 1 to 11 can be expressed as sums of its divisors 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6: as well as these divisors themselves, we have 5=3+2, 7=6+1, 8=6+2, 9=6+3, 10=6+3+1, and 11=6+3+2.

The sequence of practical numbers (sequence A005153 in OEIS) begins

- 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 18, 20, 24, 28, 30, 32, 36, 40, 42, 48, 54, ....

Practical numbers were used by Fibonacci in his Liber Abaci (1202) in connection with the problem of representing rational numbers as Egyptian fractions. Fibonacci does not formally define practical numbers, but he gives a table of Egyptian fraction expansions for fractions with practical denominators.[2]

The name "practical number" is due to Srinivasan (1948), who first attempted a classification of these numbers that was completed by Stewart (1954) and Sierpiński (1955). This characterization makes it possible to determine whether a number is practical by examining its prime factorization. Any even perfect number and any power of two is also a practical number.

Practical numbers have also been shown to be analogous with prime numbers in many of their properties.[3]

Contents |

Characterization of practical numbers

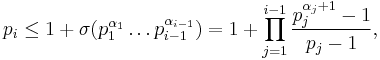

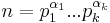

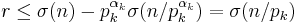

As Stewart (1954) and Sierpiński (1955) showed, it is straightforward to determine whether a number is practical from its prime factorization. A positive integer  with

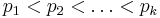

with  and primes

and primes  is practical if and only if

is practical if and only if  and, for every i from 2 to k,

and, for every i from 2 to k,

where  denotes the sum of the divisors of x. For example, 3 ≤ σ(2)+1 = 4, 29 ≤ σ(2 × 32)+1 = 40, and 823 ≤ σ(2 × 32 × 29)+1=1171, so 2 × 32 × 29 × 823 = 429606 is practical. This characterization extends a partial classification of the practical numbers given by Srinivasan (1948).

denotes the sum of the divisors of x. For example, 3 ≤ σ(2)+1 = 4, 29 ≤ σ(2 × 32)+1 = 40, and 823 ≤ σ(2 × 32 × 29)+1=1171, so 2 × 32 × 29 × 823 = 429606 is practical. This characterization extends a partial classification of the practical numbers given by Srinivasan (1948).

It is not difficult to prove that this condition is necessary and sufficient for a number to be practical. In one direction, this condition is clearly necessary in order to be able to represent  as a sum of divisors of n. In the other direction, the condition is sufficient, as can be shown by induction. More strongly, one can show that, if the factorization of n satisfies the condition above, then any

as a sum of divisors of n. In the other direction, the condition is sufficient, as can be shown by induction. More strongly, one can show that, if the factorization of n satisfies the condition above, then any  can be represented as a sum of divisors of n, by the following sequence of steps:

can be represented as a sum of divisors of n, by the following sequence of steps:

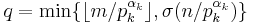

- Let

, and let

, and let  .

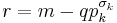

. - Since

and

and  can be shown by induction to be practical, we can find a representation of q as a sum of divisors of

can be shown by induction to be practical, we can find a representation of q as a sum of divisors of  .

. - Since

, and since

, and since  can be shown by induction to be practical, we can find a representation of r as a sum of divisors of

can be shown by induction to be practical, we can find a representation of r as a sum of divisors of  .

. - The divisors representing r, together with

times each of the divisors representing q, together form a representation of m as a sum of divisors of n.

times each of the divisors representing q, together form a representation of m as a sum of divisors of n.

Relation to other classes of numbers

Any power of two is a practical number.[4] Powers of two trivially satisfy the characterization of practical numbers in terms of their prime factorizations: the only prime in their factorizations, p1, equals two as required. Any even perfect number is also a practical number:[4] due to Euler's result that these numbers must have the form 2n − 1(2n − 1), every odd prime factor of an even perfect number must be at most the sum of the divisors of the even part of the number, and therefore the number must satisfy the characterization of practical numbers.

Any primorial is practical.[4] By Bertrand's postulate, each successive prime in the prime factorization of a primorial must be smaller than the product of the first and last primes in the factorization of the preceding primorial, so primorials necessarily satisfy the characterization of practical numbers. Therefore, also, any number that is the product of nonzero powers of the first k primes must also be practical; this includes Ramanujan's highly composite numbers (numbers with more divisors than any smaller positive integer) as well as the factorial numbers.[4]

Practical numbers and Egyptian fractions

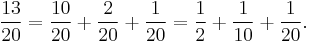

If n is practical, then any rational number of the form m/n may be represented as a sum ∑di/n where each di is a distinct divisor of n. Each term in this sum simplifies to a unit fraction, so such a sum provides a representation of m/n as an Egyptian fraction. For instance,

Fibonacci, in his 1202 book Liber Abaci[2] lists several methods for finding Egyptian fraction representations of a rational number. Of these, the first is to test whether the number is itself already a unit fraction, but the second is to search for a representation of the numerator as a sum of divisors of the denominator, as described above; this method is only guaranteed to succeed for denominators that are practical. Fibonacci provides tables of these representations for fractions having as denominators the practical numbers 6, 8, 12, 20, 24, 60, and 100.

Vose (1985) showed that every number x/y has an Egyptian fraction representation with  terms. The proof involves finding a sequence of practical numbers ni with the property that every number less than ni may be written as a sum of

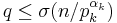

terms. The proof involves finding a sequence of practical numbers ni with the property that every number less than ni may be written as a sum of  distinct divisors of ni. Then, i is chosen so that ni − 1 < y ≤ ni, and xni is divided by y giving quotient q and remainder r. It follows from these choices that

distinct divisors of ni. Then, i is chosen so that ni − 1 < y ≤ ni, and xni is divided by y giving quotient q and remainder r. It follows from these choices that  . Expanding both numerators on the right hand side of this formula into sums of divisors of ni results in the desired Egyptian fraction representation. Tenenbaum & Yokota (1990) use a similar technique involving a different sequence of practical numbers to show that every number x/y has an Egyptian fraction representation in which the largest denominator is

. Expanding both numerators on the right hand side of this formula into sums of divisors of ni results in the desired Egyptian fraction representation. Tenenbaum & Yokota (1990) use a similar technique involving a different sequence of practical numbers to show that every number x/y has an Egyptian fraction representation in which the largest denominator is  .

.

Analogies with prime numbers

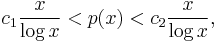

One reason for interest in practical numbers is that many of their properties are similar to properties of the prime numbers. For example, if p(x) is the enumerating function of practical numbers, i.e., the number of practical numbers not exceeding x, Saias (1997) proved that for suitable constants c1 and c2:

a formula which resembles the prime number theorem. This result largely resolved a conjecture of Margenstern (1991) that p(x) is asymptotic to cx/log x for some constant c, and it strengthens an earlier claim of Erdős & Loxton (1979) that the practical numbers have density zero in the integers.

Theorems analogous to Goldbach's conjecture and the twin prime conjecture are also known for practical numbers: every positive even integer is the sum of two practical numbers, and there exist infinitely many triples of practical numbers x − 2, x, x + 2.[5] Melfi also showed that there are infinitely many practical Fibonacci numbers (sequence A124105 in OEIS); the analogous question of the existence of infinitely many Fibonacci primes is open. Hausman & Shapiro (1984) showed that there always exists a practical number in the interval [x2,(x + 1)2] for any positive real x, a result analogous to Legendre's conjecture for primes.

Notes

- ^ Margenstern (1991) cites Robinson (1979) and Heyworth (1980) for the name "panarithmic numbers".

- ^ a b Sigler (2002).

- ^ Hausman & Shapiro (1984); Margenstern (1991); Melfi (1996); Saias (1997).

- ^ a b c d Srinivasan (1948).

- ^ Melfi (1996).

References

- Erdős, Paul; Loxton, J. H. (1979), "Some problems in partitio numerorum", Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society (Series A) 27 (03): 319–331, doi:10.1017/S144678870001243X.

- Heyworth, M. R. (1980), "More on panarithmic numbers", New Zealand Math. Mag. 17 (1): 24–28. As cited by Margenstern (1991).

- Hausman, Miriam; Shapiro, Harold N. (1984), "On practical numbers", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 37 (5): 705–713, doi:10.1002/cpa.3160370507, MR0752596.

- Margenstern, Maurice (1984), "Résultats et conjectures sur les nombres pratiques", C. R. Acad. Sci. Sér. I 299 (18): 895–898. As cited by Margenstern (1991).

- Margenstern, Maurice (1991), "Les nombres pratiques: théorie, observations et conjectures", Journal of Number Theory 37 (1): 1–36, doi:10.1016/S0022-314X(05)80022-8, MR1089787.

- Melfi, Giuseppe (1996), "On two conjectures about practical numbers", Journal of Number Theory 56 (1): 205–210, doi:10.1006/jnth.1996.0012, MR1370203.

- Mitrinović, Dragoslav S.; Sándor, József; Crstici, Borislav (1996), "III.50 Practical numbers", Handbook of number theory, Volume 1, Mathematics and its Applications, 351, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 118–119, ISBN 9780792338239.

- Robinson, D. F. (1979), "Egyptian fractions via Greek number theory", New Zealand Math. Mag. 16 (2): 47–52. As cited by Margenstern (1991) and Mitrinović, Sándor & Crstici (1996).

- Saias, Eric (1997), "Entiers à diviseurs denses, I", Journal of Number Theory 62 (1): 163–191, doi:10.1006/jnth.1997.2057, MR1430008.

- Sigler, Laurence E. (trans.) (2002), Fibonacci's Liber Abaci, Springer-Verlag, pp. 119–121, ISBN 0-387-95419-8.

- Sierpiński, Wacław (1955), "Sur une propriété des nombres naturels", Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata 39 (1): 69–74, doi:10.1007/BF02410762.

- Srinivasan, A. K. (1948), "Practical numbers", Current Science 17: 179–180, MR0027799, http://www.ias.ac.in/jarch/currsci/17/179.pdf.

- Stewart, B. M. (1954), "Sums of distinct divisors", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 76 (4): 779–785, doi:10.2307/2372651, JSTOR 2372651, MR0064800.

- Tenenbaum, G.; Yokota, H. (1990), "Length and denominators of Egyptian fractions", Journal of Number Theory 35 (2): 150–156, doi:10.1016/0022-314X(90)90109-5, MR1057319.

- Vose, M. (1985), "Egyptian fractions", Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society 17 (1): 21, doi:10.1112/blms/17.1.21, MR0766441.

External links

- Tables of practical numbers compiled by Giuseppe Melfi

- Practical Number at PlanetMath.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Practical Number" from MathWorld.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||